Chinchilla Types, Or Species

Articles

- Chinchilla brevicaudata (Short-Tailed Chinchilla) or .doc – Animal Diversity Web

- Chinchilla lanigera (Long-Tailed Chinchilla) or .doc – Animal Diversity Web

- Family Chinchillidae (chinchillas and viscachas) or .doc – Animal Diversity Web

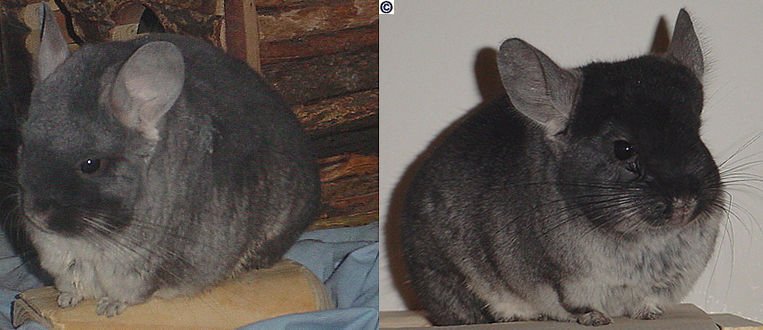

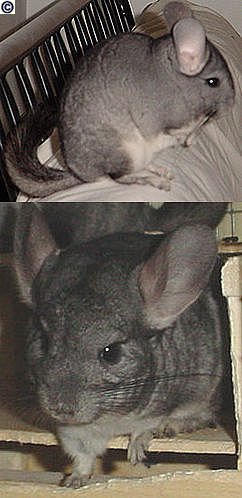

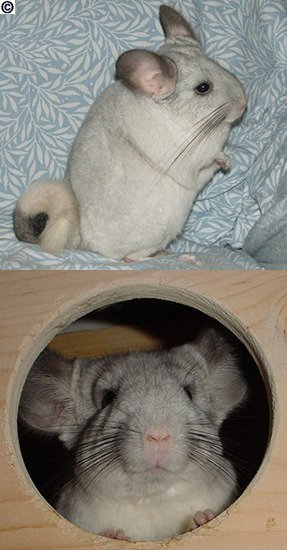

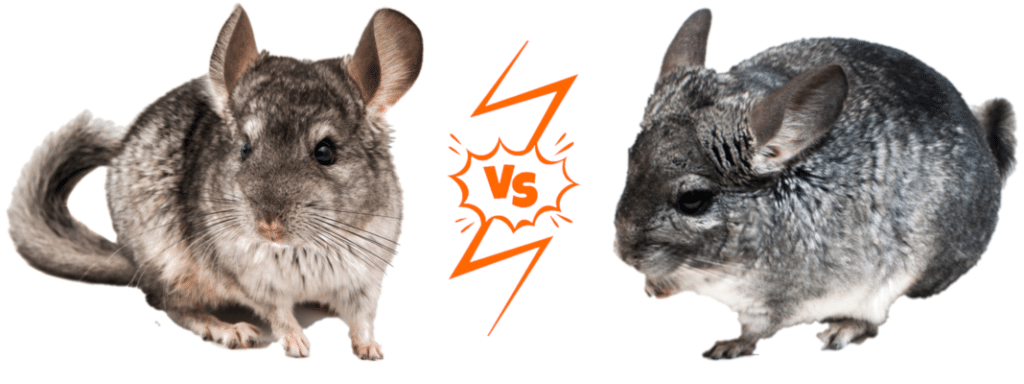

Photos of the Chinchilla Species: C. brevicaudata and C. lanigera

Domestic chinchillas, a result of cross-breeding between the two species

- Chinchilla brevicaudata traits:

- Chinchilla lanigera traits:

- Chinchilla lanigera vs Chinchilla brevicaudata:

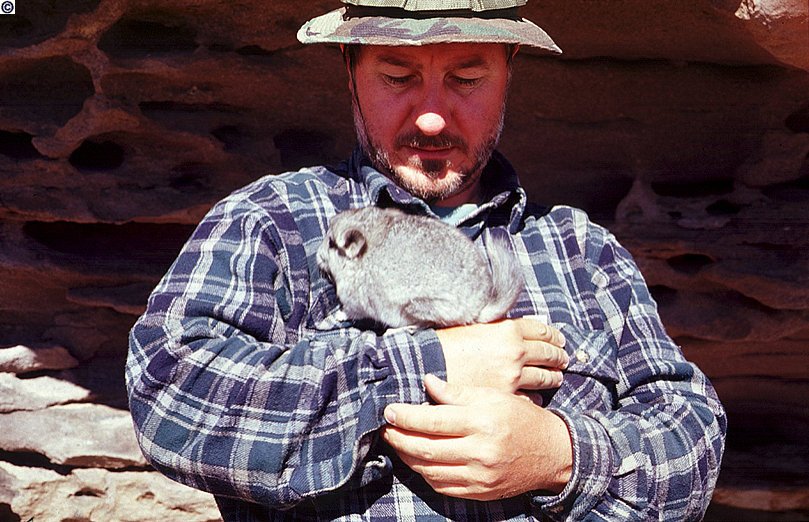

Wild chinchillas (Viscachas are not wild chinchillas)

- Photos by Save the Wild Chinchillas

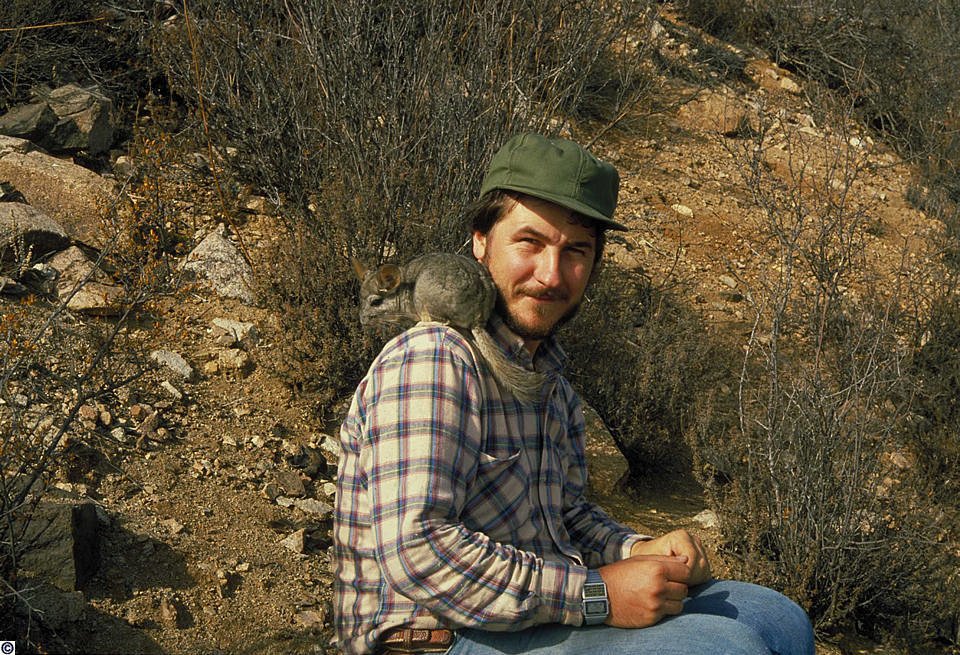

- Photos by Jaime E. Jiménez, PhD, carefully capturing a wild Chinchilla brevicaudata and Chinchilla lanigera:

Jaime E. Jiménez, PhD, carefully capturing a wild Chinchilla brevicaudata wild Chinchilla brevicaudata wild Chinchilla brevicaudata wild Chinchilla brevicaudata wild Chinchilla brevicaudata Jaime E. Jiménez, PhD, and a wild Chinchilla brevicaudata wild Chinchilla lanigera wild Chinchilla lanigera Jaime E. Jiménez, PhD, and a wild Chinchilla lanigera

Species Description

Some older rancher-authored books describe a variety of chinchilla “types,” but that categorizing was based on layman observation of variations within the species and today only two species are universally and officially recognized as being truly distinct, separate species: Chinchilla lanigera and Chinchilla brevicaudata.

1. Chinchilla Brevicaudata, The Short-Tailed Chinchilla

Brevis, as they are often referred to, were once plentiful in the high altitudes of the Andes mountains, where they occupied very barren and inhospitable areas such as those that the remaining brevis still inhabit in the north of Chile: Llullaillaco Volcano, Salar Punta Negra. C. brevicaudata, besides having a short tail, is distinguished from C. lanigera by having smaller and rounder ears, a puggish face and broader head, thick neck, and a body shape that is blocky, stout, and usually larger and heavier than C. lanigera (photo of brevi traits in the domestic chin). The coat of purebreds was said to have a brownish cast and wavy texture. The gestation period of brevis is slightly longer than that of lanigeras, lasting 128 days.

2. Chinchilla Lanigera, The Long-Tailed Chinchilla

C. lanigera once commonly populated the mid and lower range of the Andes. They are presently known to reside only in Chile, populations exist both in and near the Las Chinchillas National Reserve. Lanigeras have a long tail, longer and larger ears than C. brevicaudata, a face that is more pointed and a body shape that is narrow, slender, and usually smaller and lighter than C. brevicaudata (photo of lanigera traits in the domestic chin). Their coat is said to have ranged in color from deep bluish hues to brown. The gestation period for lanigeras is 111 days, this is also the usual gestation period for domestic chinchillas, which are a result of cross-breeding between C. brevicaudata and C. lanigera.

Scientific Classification, and How Chinchillas Differ from Viscachas

Also see: Taxonomy (doc)

There has been some confusion in the pet chinchilla community about wild chinchillas and viscachas, and the two species’ confusing scientific classification. The Family “Chinchillidae” contains two separate types of animals (Genus Chinchilla and Genus Viscacha) and six species are grouped under that in the following manner: in the Genus Chinchilla, there is Chinchilla lanigera and Chinchilla brevicaudata and in the Genus Viscacha, there is the Northern Viscacha, Southern Viscacha, Wolffsohn’s Viscacha, and Plains Viscacha.

Viscachas are a different animal than chinchillas, they’re just grouped together in the same Family classification in the same way that okapis are different from giraffes but they’re both in the Family “Giraffidae.” The Family Chinchillidae and the Family Giraffidae simply take the name of one of the Genus under them, perhaps because the viscachas and okapis were added to their respective families at a later date.

There are also breeds of cat called “Chinchilla Cat” and breeds of rabbit called “Chinchilla Rabbit,” but they are no relation to chinchillas other than being fellow mammals.

Hyperlinks in the right column go to Wikipedia to elaborate on the distinguishing attributes of the classifications:

| Kingdom | Animalia |

| Phylum | Chordata |

| Class | Mammalia |

| Order | Rodentia |

| Suborder | Hystricognathi |

| Family | Chinchillidae |

| Genus | Chinchilla |

| Species | Chinchilla lanigera & Chinchilla brevicaudata |

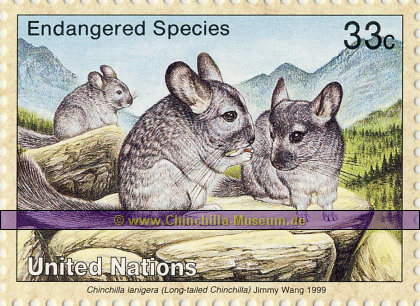

Wild Chinchilla Conservation Status For Short And Long-tailed Chinchillas

Also see: Chinchilla Lexicon’s chinchilla stamp collection

Wild chinchillas of both types have been protected in their native habitat since 1910, when the treaty “between Chile, Bolivia, Argentina and Peru, the main exporters of chinchilla fur… banned the hunting and commercialization of chinchillas.” Illegal trapping continued for some time afterward, however, a result of difficulties encountered with enforcing the law over such a formidable expanse of challenging terrain. (Extirpation and Current Status of Wild Chinchillas) The Endangered Species Handbook (.pdf) also reports on the current status of wild chinchillas.

From charity organization Save the Wild Chinchillas: About STWC, a PowerPoint presentation (.ppt), Conservation Article, An STWC volunteer’s story, STWC Newsletters (.pdf) for 2007 & 2008

Chinchilla Brevicaudata, The Short-Tailed Chinchilla

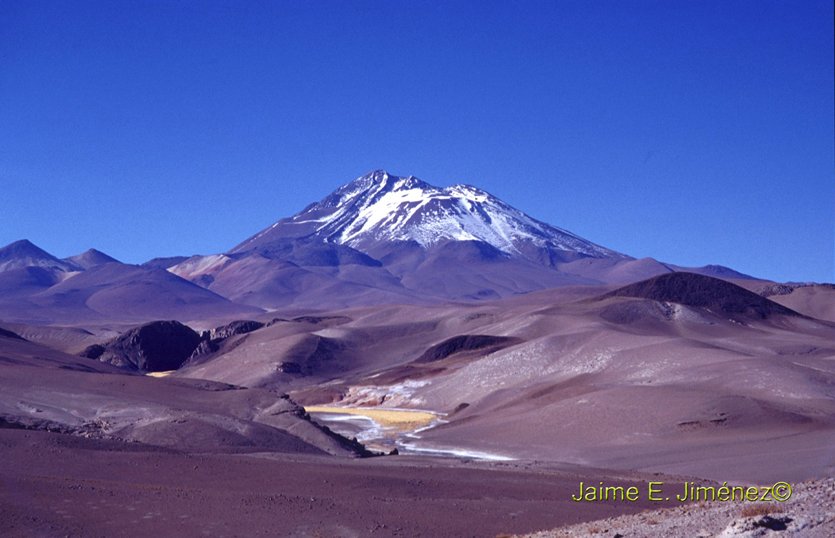

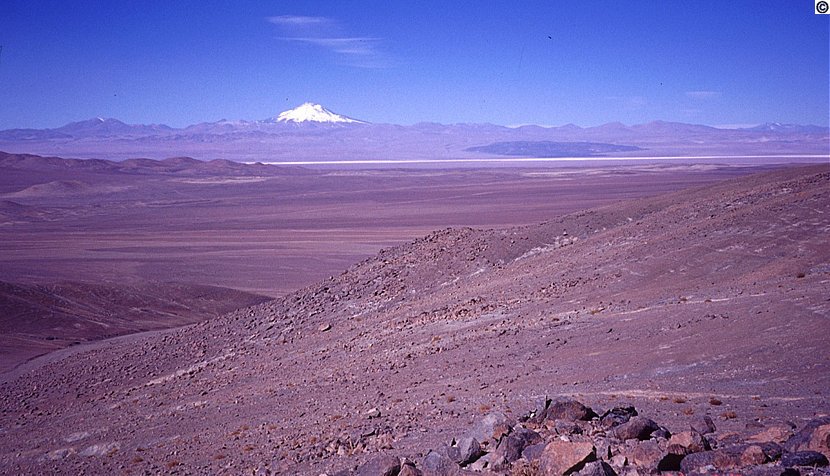

In 2001, about a dozen brevicaudatas, thought to be extinct in the wild, were rediscovered in the north of Chile by Jaime E. Jiménez, Ph.D. He took these pictures of their habitat: Llullaillaco Volcano and nearby Salar Punta Negra.

Llullaillaco Volcano by Jaime E. Jiménez (Chinchilla habitat) Salar Punta Negra by Jaime E. Jiménez (Chinchilla habitat)

“The short-tailed chinchilla was classified as Critically Endangered (CR A1cd) on the 2006 IUCN [that status remains as of 2008. The International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources is better known as IUCN] Red List of Threatened Species…

“The species is on Appendix I of CITES [prohibiting international trade] and has been protected by law in Chile since 1929, although, as mentioned above, this law has proved difficult to enforce. Currently, almost all chinchilla fur comes from farmed animals, and recent improvements in the quality of captive chinchilla fur have reduced pressure on the remaining wild populations. However, it is also likely that commercial breeding activities have stimulated the demand for live wild chinchillas to improve the genetic variability of captive stocks. Indeed, several of the eleven wild short-tailed chinchillas captured in 2001 were transferred to a breeding program in which they were used to boost the genetic diversity of the captive population…

“Further surveys are needed to establish the location of wild populations of this species. There are unconfirmed reports from the 1970s of the short-tailed chinchilla in the Lauca National Park in Chile.” (ref– excerpts from edgeofexistence.org)

Chinchilla Lanigera, The Long-Tailed Chinchilla

Chinchilla lanigera, as of 2008, is classified as Critically Endangered on the IUCN [The International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources is better known as IUCN] Red List of Threatened Species. Chinchilla lanigera is protected under Appendix I of CITES, prohibiting international trade.

According to Animal Diversity Web (.doc), “Chinchillas are now protected by law in their natural habitat, yet hunting of this animal for its fur continues in remote areas, which makes enforcement hard. Populations of C. lanigera have also dwindled because of the burning and harvesting of the algarobilla shrub in the lower altitudes. Fewer than 10,000 C. lanigera is thought to have survived in the wild, and attempts to reintroduce chinchillas into the wild have failed.”

The Long-Tailed Chinchilla’s last haven in the wild is Las Chinchillas National Reserve in Chile, where small populations near and inside the reserve eke out an existence.

Recent Wild Chinchilla Research And Links: History, Life In The Wild

Research

1983: Chart of plants consumed by the wild Chinchilla lanigera, based on fecal studies

by Save the Wild Chinchillas:

2008: Searching for Wild Chinchillas (.doc)

formed in 1996, STWC’s Field Notes

by Jaime E. Jiménez, PhD, et al:

2004: Chinchilla laniger (.pdf)

2002: Seasonal food habits of the endangered long-tailed chinchilla (Chinchilla lanigera) (.pdf)

1995: Conservation of the Last Wild Chinchilla (Chinchilla lanigera) Archipelago: A Metapopulation Approach (.pdf)

1995: The Extirpation and Current Status of Wild Chinchillas Chinchilla lanigera and C. brevicaudata (.pdf)

1992: Numerical and functional response of predators to a long term decline in mammalian prey at a semi-arid Neotropical site (.pdf)

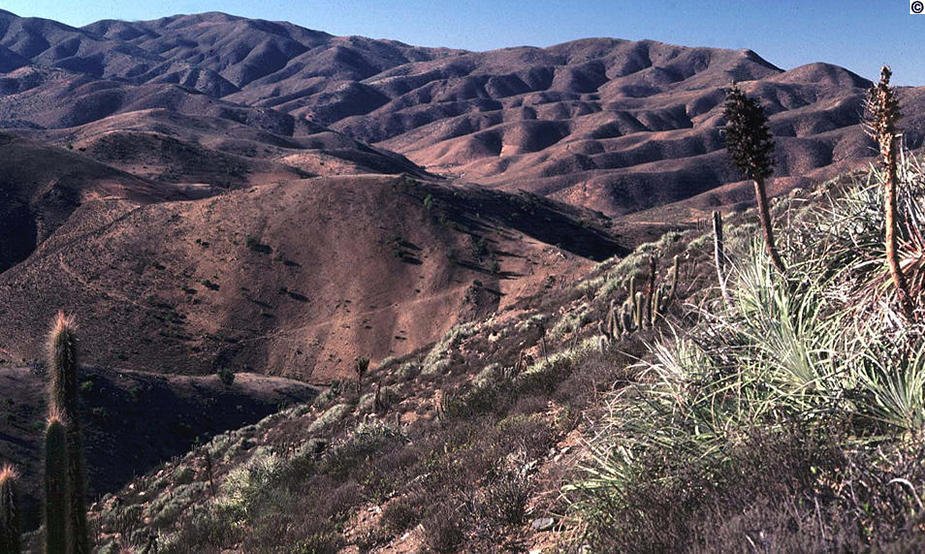

Las Chinchillas National Reserve In Chile

Reserva Nacional Las Chinchillas, Chile: “since 1983, the only reservation which protects the Chilean chinchilla (Chinchilla lanigera) in the world has been dedicated to the preservation of this endangered species. The reservation is located 15 kilometers to the northeast of Illapel in the Choapa Valley. Some 6,000 chinchillas live here in this unique habitat below the leaves of the Puyo cactus on rocky slopes. The presence of such special flora and fauna in various stages of recuperation has made the Chinchillas National Reservation an ideal place for study, investigation, and environmental education, it is also supported by the World Wildlife Federation.

Sights And Cultures Of The Andes

The chinchilla’s original habitat was the Andes mountain range as it crosses parts of these South American countries: Argentina, Bolivia, Chile, and Peru. Today, chinchillas are known to exist only in Chile.

“The past distribution of chinchillas is unclear. Grau (1986) and Housse (1953) reported that chinchillas were found from Taka, Chile (35° 30’S), north to Peru, and longitudinally from the Chilean coastal hills to the Andes and puna of Argentina, Bolivia and Peru (Osgood, 1943). Gay (cited in Osgood, 1943) concurred with Albert (1901) and Opazo (1911) that chinchillas were not found south of the Choapa river (32°S). Recently, Jiménez (1990) came to the same conclusion. Walker (1968) mistakenly reported that chinchillas occurred as far south as 52°S.

“Because only one chinchilla species was recognized in the past there is no evidence of whether the two species coexisted in sympatry in some parts of their past distribution. However, Grua (1986) suggests that both species may have coexisted in sympatry around Potrerillos. This region would have corresponded to the northern limit of the Long-Tailed Chinchilla distribution and to the southern limit of the Short-Tailed Chinchilla (but see Grau, 1986).” (ref- .pdf, Extirpation and Current Status of Wild Chinchillas)

“Currently the Long-Tailed Chinchilla exists only near Illapel (31°38’S, 71° 06’W; probably the southern range of their past distribution) in the Reserva Nacional Las Chinchillas, and in an isolated population about 100 km north of Coquimbo (29° 33’S, 71°04’W, Jiménez, 1990, 1993).” (ref- .pdf, Extirpation and Current Status of Wild Chinchillas)

Photos by Jaime E. Jiménez, PhD, of the Andes mountains region:

“The mountains Macón, Aracar and Lllullaillaco are sanctuaries where height rest ancestors of some of the most prosperous civilization originating from history Incas. The Llullaillaco: is located at 24° 43′ latitude south and 68 ° 32′ latitude west, northwest la Republica Argentina on the border with Chile. It stands at 6,739 meters above sea level, on what it considers one of the highest volcanoes in the world. It belongs to the western Andean mountain range and is located west of the Salar Arizaro, and the Salina of Llullaillaco and east of Punta Negra salt flats, in the natural context of the driest deserts in the world.

“Inca Sanctuary: A group of Inca ruins at the top of a volcano Llullaillaco represents the highest archaeological site in the world. Along with the slopes of the volcano, is one of the ceremonial centers of high mountain most complete and best-preserved of the Andes. The extreme altitude may explain the choice that the Incas made the summit as a stage to conduct a ceremony utmost importance, the capacocha or slaughter of human beings in its sacredness. (www.maam.org.ar)” (Google translation of “Tolar Grande City That Makes A Homeland,” lahoradesalta.com.ar)

The word “chinchilla” is rooted in the language and culture of the Andes.

There are a few possible etymological explanations, the most common being that chinchilla means “little Chincha” and was coined by the Spanish who associated the animal with the Chincha (NOT “Chinta”) indians, who used them for food and clothing. Another possibility is, “The common name, chinchilla, may derive from Quechua words chin meaning silent, sinchi meaning strong or courageous (Grau 1986), and a diminutive Quechua lla. Together, chinchilla would mean the strong, silent little (Aleandri 1998). The name laniger is from Latin, meaning woolly.” (ref- .pdf, Chinchilla laniger) The least mentioned possibility is: “1593, from Sp., lit. “little bug” (see chinch); probably an alteration of a word from Quechua or Aymara.” (ref– Online Etymology Dictionary)

The Great Mf Chapman Hoax

Also see: Popular Science magazine article from 1933, containing an interview with MF Chapman: “Three American Chinchilla Farms Produce Most Costly Furs.”Article pages: 1, 2, 3 (enlarge in browser window), reproduced here with permission from modernmechanix.com.

The MF Chapman story is also mentioned in this 1937 article (.doc), which is just one illustration of the fact that NOT “all chinchillas today” are descended from MF Chapman’s original twelve (the number that arrived in California). The myth of Chapman’s animals being the original stock from which all captive chinchillas came into being is yet another story told for the purpose of idolizing the founding father of the commercial chinchilla fur industry.

From the fur industry’s public relations machine comes the “romantic story” (ref– Canchilla Associates and other sources including the out-of-print book authored by Reginald G. Chapman, published by The Chapman Chinchilla Farm and titled, “The Romantic Story of the Chinchilla” ) of how chinchillas were “saved from extinction” (ref- 1, 2, etc.) by the fur industry founder, the first successful commercial chinchilla fur farmer: Mathias F. Chapman. In these times when the subject of fur is often a rancorous topic, the fur industry has taken it upon themselves to rewrite history, to give Chapman’s adventures a new spin. His carefully hyped celebrity status has been peddled far and wide in books and across the internet (ref- 1, 2, 3, etc.) by the fur industry and its associates, to the point where sheer repetition has led some people to mistake these retellings for sound historical fact; even some pet chinchilla sites have naively carried the propaganda.

When the fur industry speaks of MF Chapman, history is suddenly reduced to a marketing tool for converting their image from that of ruthless, exploitative hunters responsible for nearly wiping chinchillas off the face of the earth (ref– this is established fact), to that of passionately dedicated conservationists who “saved” the chinchilla. This absurd deception is accomplished by storytelling embellished with a great deal of heavily biased interpretative value (“spin”) so that the fur industry’s founding father emerges as a great animal lover who “saved” chinchillas from extinction just because he took a liking to them. The fur industry is counting on the probability that people will not know all the facts and that a “romantic story” will have more consumer appeal than the hard truth. They’re hoping that people won’t know enough of what really went on to realize that Chapman took government-protected chinchillas out of their native habitat so that he could cage them in captivity where they could be more conveniently killed and exploited for their fur and his gain.

Annmarie Barrie’s book, “Guide to Owning a Chinchilla,” (p.7) illustrates this glamorization perfectly, “M.F. Chapman, a mining engineer from California, was working in Chile in 1918. He purchased a chinchilla as a pet and took a real liking to it. Subsequently, he envisioned raising a whole herd of chinchillas.” The older and more authoritative accounts, the ones written by ranchers back in the day who had learned Chapman’s story from the source or from his direct associates, all say the same thing, that one day a native Chilean showed up with a live chinchilla and that sparked Chapman’s interest in farming them in captivity for their fur. The personal interview with Chapman in the Popular Science article mentioned above confirms that Chapman envisioned chinchillas as a business investment, not a heartwarming conservation opportunity.

Often repeated, especially on pet chinchilla sites (ref- 1, 2, etc.), is the added admonishment to pet chinchilla owners that they are indebted, “owe thanks” to MF Chapman for their enjoyment of chinchillas as pets today. An example of this not-so-subliminal fur industry plug is modelled in “The Chinchilla Handbook” by Sharon L. Vanderlip, DVM (p.5): “…an American mining engineer working for the Anaconda Copper Company in Chile managed to save C. laniger. If it were not for the extraordinary efforts of Mathias F. Chapman, you would not have your cuddly pet today.”

This article presents a careful analysis of historical facts that are usually omitted (or given a make-over) in the typical retelling of the MF Chapman story.

Regardless of one’s loyalty or bias regarding pelting and the fur industry, facts are still facts, and as such they will always trump self-serving propaganda. The historical facts exposed in this article with a literal, as opposed to manipulative interpretation, will hopefully expedite the retirement of the fur industry’s most ridiculous farce.

It’s worth mentioning that anyone who wishes to mistake this article for “animal rights propaganda” should take a close look at what the ChinCare webmasters have done and continue to do for chinchilla rescue and to save ranch chinchillas. We are completely informed of both sides of the “pet versus pelt” issue and we strongly oppose BOTH pelting AND animal rights extremism. For years we have set aside differences to work directly with ranchers so they don’t have to pelt, thereby saving ranch chinchillas lives. We only care about putting the truth and the chins first.

For this article we researched nine separate written accounts (from our large chinchilla reference library of scholarly and rancher-authored books (.doc), and including the Popular Science article mentioned above) of MF Chapman’s exploits in addition to innumerable internet pages (since 2002 we’ve hand-reviewed all English language pet chinchilla care sites- over 700 as of 2008- on the web for the educational purposes of this site) on the subject, and our sources are cited below.

FACT 1: Chinchillas had enjoyed government legal protection in their native territories since 1910, with very limited exceptions.

- “The treaty of 1910 between Chile, Bolivia, Argentina and Peru, the main exporters of chinchilla fur, was the first international effort to protect the species (Grau, 1986). It banned the hunting and commercialization of chinchillas.” (ref- .pdf, Extirpation and Current Status of Wild Chinchillas)

- “Early in the 20th century, populations of both species–the Long-tailed (Chinchilla laniger) and the Short-tailed (Chinchilla brevicaudata) Chinchilla, collapsed. In 1910, an agreement was signed by Andean countries where the two chinchilla species occur, to prohibit capture, trade and export (IUCN 1994).” (ref- .pdf, Endangered Species Handbook)

- After the 1910 treaty, Bolivia, Chile and Argentina allowed extremely limited trapping by government permission only for the purpose of establishing captive breeding facilities, these endeavors met with limited success or failure. (ref- .doc, Clarke’s “Modern Chinchilla Fur Farming,” p.15 and Bickel’s “Chinchilla Handbook,” p.47)

FACT 2: MF Chapman arrived in Chile in 1918 (after the 1910 law) as a mining engineer for the Anaconda Copper Company and removed a dozen of the best (of the last) chinchilla specimens from the wild.

- MF Chapman “got a permit from the Chilean Government to trap his animals in 1918.”

(ref- .doc, Clarke’s “Modern Chinchilla Fur Farming,” p.13)

…This is the only written source in our research that alludes to obtaining permission to trap, the other resources simply mention that he went about trapping. Considering that poaching was still a problem at the time (ref- .pdf, Extirpation and Current Status of Wild Chinchillas), it is quite possible that this trapping was conducted illegally. Indeed, we later discovered this source (ref-.pdf, Notes on the Genus Chinchilla) that makes discreet but unmistakable reference to Chapman’s farm, and states that the chinchillas were smuggled out of Chile.

- “Chapman’s records show a search for chinchillas in 1919: ‘A party of twenty Indian trappers combed the mountains for three years to get a dozen suitable animals for Chapman. During that period some of the Indians didn’t even see a chinchilla.'” (ref- .doc, Medow’s “The Chinchilla,” p.6)

…Written sources sometimes vary on the count and time, e.g., 23 trappers over the course of four years, etc. The Popular Science interview named above quotes Chapman, “Soon I had twenty-three Chileans and Indians on the trail. Yet the net result of all that hunting was a dozen animals. I finally left South America with eleven animals; and arrived at Los Angeles [in 1923] with a dozen. An expectant mother had given birth to two while on the high seas and we managed to save one of them.”

- “Since hunting chinchillas or even possession of their pelts was already prohibited by law, he had great difficulties in obtaining the necessary export permit. He was given an export license for only 11 of the 17 animals he owned. He selected the most attractive and strongest animals, the previously mentioned eight bucks and three females.” (ref- .doc, Bickel’s “Chinchilla Handbook,” p.55) …Sources vary, some record seven males and four females

FACT 3: MF Chapman began the modern chinchilla fur farming industry by founding the first successful captive breeding facility in California, USA. His success led to the spread of chinchilla fur farming throughout North America and Canada, reaching Europe after WWII.

- “…this interest [in chinchillas] gradually turned to a desire to return to the United States with as many chinchillas as he could and to establish there his own ranch devoted to the raising of these animals.” (ref- .doc, Clarke’s “Modern Chinchilla Fur Farming,” p.13)

- “Had it not been for the endeavors of an American mining engineer, M.F. Chapman… there might not have been any chinchilla industry today.” (ref- .doc, Houston and Prestwich’s “Chinchilla Care,” 1962 edition, p.17)

- “Following the success that Chapman had with his captive breeding programme, extensive ‘ranch breeding’ began throughout North America and Canada. It was not until after World War 2 that this spread to Europe.” (ref- Chinchillas2Home)

A Common Sense Conclusion Based on Historical and Present Facts

MF Chapman removed the best of the last of the wild chinchillas from their native habitat, just as they had begun to receive rigorous, effective government protection (legislation had been passed in 1898 and stricter legislation than the 1910 treaty mentioned in Fact 1 was passed in 1929- ref- .pdf, Extirpation and Current Status of Wild Chinchillas. Today the wild chinchilla is protected by CITES) that in the long run would prove to REALLY save them and prevent their extinction in the wild.

When the fur industry depicts MF Chapman as the hero who “saved” chinchillas from extinction, they first appeal to the well-known fact that chinchillas had been nearly exterminated by the turn of the 20th century. From there the implication is made that chinchillas were continuing to go extinct, as if this were happening “naturally,” the wild chinchilla just inexplicably vanishing, unprotected, from its native habitat until the “savior,” MF Chapman, came along.

But this is not the case, because the cause of the chinchilla’s near-extermination was overhunting by the fur industry and government protection had put a stop to that YEARS before Chapman arrived in Chile. Therefore, Chapman did absolutely no favors for chinchillas when he entered the scene and, in the name of the fur industry once again, hunted down and removed the BEST OF THE LAST (Fact 2) from their native habitat. This additional hunting after they were under government protection did not “save” the chinchilla, it unquestionably contributed to its EXTINCTION in the wild. Contributing to the extinction of a species in its (protected!) native habitat is NOT “saving” it.

The loss of those remaining prime (breeding) specimens, that it took a large team of trappers YEARS to find, had direct and dire consequences for the remaining wild chinchilla population; their numbers have not rebounded and they remain endangered to this very day. Nevertheless, the fact that the species has persisted in spite of losing those superior breeding specimens proves beyond a doubt that the chinchilla would NOT have “become extinct” if MF Chapman had never intervened to “save” them. Quite the contrary, they would have obviously been MUCH better off! If the wild chinchilla population had retained the Chapman chinchillas, they would have had a larger gene pool and stronger, more robust stock from which they could have produced in greater abundance and today they’d all be living free in the Andes mountains the way that nature intended. Instead, most captive chinchillas today still live on fur farms.

Of course, we know what the fur industry and its associates really mean when they insist that MF Chapman “saved” the chinchilla from extinction. They are promoting the “sustainable use” lie, claiming that removing an endangered species from its native habitat so that man can farm and exploit it in captivity is “saving” it. This is, of course, illogical, especially considering that chinchillas were receiving government protection in their native habitat and on fur farms they would be killed for their fur. As Steve Irwin put it, “Since when has killing animals saved a species?” (ref– crocodilehunter.com.au)

If MF Chapman had really wanted to “save” the chinchilla from extinction, he would have acted as a wildlife conservationist (championed measures to protect them in their own environment), NOT as a hunter/ trapper/ fur farmer. But Chapman himself made no pretense of heroism, he wasn’t trying to “save” the chinchilla. He was interested in them for their pelts, just as he’d raised rabbits and squirrels “for their hides” in his youth in Oregon, so once in Chile “…while living among the native Indians and Chileans [Chapman] became interested in the chinchillas. He had heard great tales of their former high position in the international fur trade.” (quotes- Popular Science interview)

MF Chapman’s success with his captive breeding facility in California was the forerunner to the sad state that most chinchillas around the world (where pelting is still profitable, in the U.S. it is not and in some countries it has been outlawed) find themselves in today: trapped in tiny cages on fur farms with nothing to do but sit and wait their turn to be killed at about a year old, and killed, not “euthanized;” the neck-breaking or electrocution of young, healthy animals is not “euthanasia”.

From the chinchilla’s standpoint, to be tossed from the frying pan (killed for their fur in the wild) into the fire (killed for their fur in captivity) is anything BUT “salvation.” At least in the wild they experienced the joys of freedom, exercise and herd companionship and had some small chance to run and hide to potentially escape being killed, but when raised on a fur farm they don’t get that quality of life (freedom, some control over their own existence), and death is inescapable. Even those who become pet chinchillas can’t always count on reliable good care that will cover their long lifespan. The fur industry’s biased interpretation of MF Chapman as “chinchilla savior” is ludicrous, false and can be duly scrapped on all (wild and captive) levels.

The evolution of chinchillas as pets took place decades after MF Chapman’s trip to Chile (in the 1980’s, when the increase in pet care books marked the rise in popularity of chinchillas as pets), and their widespread popularity as pets is not attributable but only INCIDENTAL to the spread of the commercial chinchilla fur industry around the globe. The fur industry and its associates did not initiate or popularize the pet movement, on the contrary many vehemently opposed it, it wasn’t until after the profitability of pelting in the U.S. and elsewhere sharply declined in the 1990’s that the pet market gained recognition by ranchers who realized its money-making potential. For instance, even as far forward as January 5, 1993, the Empress Chinchillla handbook states in their Code of Ethics: “Do not participate in the sale, production, or ownership of chinchilla for pets.”

We know of new pet clubs that were harassed until they made peace by promoting pelter club (ECBC, MCBA were formed to support the fur industry) literature and events. When pelter clubs reluctantly admitted pet breeders (those clubs are for breeders), it was a patronizing gesture done entirely on their terms to continue and extend their control and influence; members then and now are required to sign a pro-pelting contract that advances the clubs’ agenda. Pelting and the focus on exploiting chinchillas as a product and a means to an end, either for profit or club accolades, pervades the clubs’ attitude, policies and practices despite the fact that PET breeders now hold the majority membership in both ECBC and MCBA.

Further example that the fur industry did not initiate or popularize the pet movement is evidenced by the following anti-pet statement made by the Chinchilla Industry Council, a fur industry organization in which ECBC and MCBA hold governing roles: “The C.I.C. has gone on record as unanimously condemning the practice of selling chinchilla as pets. It was felt that this has drawn unfavorable attention to the pelting industry by the animal rightists and could possible in the future cause the outlawing of chinchilla pelting, as has already occurred in the U.K.” (ref- chinchillaindustrycouncil.com)

In the preface to Mosslacher’s “Breeding and Caring for Chinchillas,” Mosslacher, a rancher, scathingly declares in several passages the, “you [pet community] owe us AND we [ranchers, fur industry] were here first” sentiment that has been widely echoed by the fur industry and its associates, as if their contribution to the knowledge of chinchilla care and breeding was anything more than the usual investment in product that they made for their own benefit. There is a loaded antipathy toward the pet community in Mosslacher’s comments, which calls to mind those U.S. ranchers who chose to end their pelting business by killing and pelting every last animal in their herd so that none would end up as pets, “Without the fur farms you probably would not have your pet chinchilla, as the original pet stock- and much of the present pet stock still- was derived from culls and other animals unwanted by chinchilla pelt farmers… So remember just where your pet chins come from and why they are available in the first place.” (ref- .doc, Mosslacher’s “Breeding and Caring for Chinchillas,” p.9)

The popularity of chinchillas as pets today is attributable SOLELY to the chinchillas themselves, who by their very nature, against hostile odds, made people take a second look and notice the personality under the fur. By their own merit chinchillas captured human affection and regard, they distinguished themselves as not “just another” fur farmed animal (e.g., sable, mink, fox, etc., have not become popular in the pet sector), and they did this from behind cage bars with nothing more than the bare appeal of their own intelligent, sociable and endearing character. Chinchillas crossed the line from fur-producing commodity to beloved pet by winning people over “in spite of,” not “thanks to” MF Chapman and the fur industry. For those of us in the pet community who know and genuinely value these gentle, wonderful creatures, there is no doubt that it is the chinchillas alone who deserve the credit for our enjoyment of their company today.

In summation, as we have proven here by revealing objective, historically documented facts that clearly contradict the romanticized interpretation of MF Chapman’s exploits: While Chapman may be regarded as a figurehead and “hero” for the fur industry, by being the first to successfully raise and commercialize chinchillas for their fur in captivity, and while this contribution may have led to chinchillas being raised on fur farms throughout the world, MF Chapman did not “save” the chinchilla from extinction in any sense of the word, and there is no “debt of gratitude” owed to either Chapman or the fur industry by chinchillas or their pet owners today.